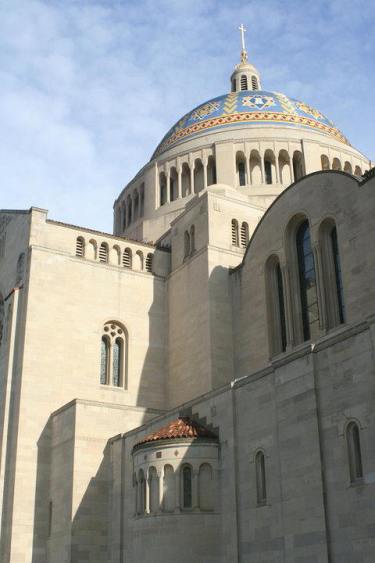

The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception... Photo by Laney Riley.

...is a fine example of Byzantine-Romanesque architecture. Photo by Laney Riley.

The Shrine and the Cathedral

One unique distinctive of the city of Washington is its relatively low profile. The capital of the greatest nation on the face of the Earth is a city without skyscrapers. New York and Chicago, the great engines of finance and commerce, thrust their architectural presence into the sky while the nation's capital's relatively modest scale defers to iconic buildings that speak of the history and aspirations of her people.

It is widely believed that the legislation controlling building heights was put in place to make sure the Washington Monument would remain the tallest building in the city. The actual legislation has to do with the height of buildings in relation to the width of the streets they occupy.

The Height of Buildings Act of 1910 restricts all buildings in Washington D.C. to being no higher than the width of the adjacent street plus 20 feet. A building on a street that is 130 feet wide can only be 150 feet tall. To be taller than the 555 foot Washington Monument without violating this law, a building would need to be on a street that is over 535 feet wide.

The result is a city who's outlying neighborhoods open to vistas of splendid shrines and cathedrals. Her Northern neighborhoods are crowned by two architectural treasures: the National Cathedral and the the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception.

Pierre Charles L'Enfant's original vision for the city, based on the palace and garden of Versailles, lends itself well to a garden city punctuated by such fine monuments. The gothic National cathedral brings to mind the great churches of Europe.

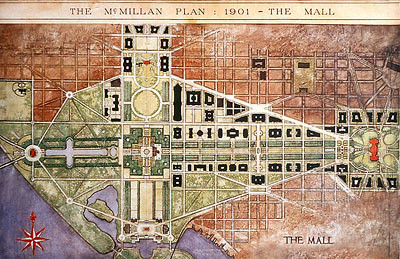

The McMillan Plan.

Pierre Charles L'Enfant's "Plan of the Federal City,” drawn in 1792,set aside a prominent site for a "great church for national purposes." Today the National Portrait Gallery stands in that place. It was not until 1891 that a meeting was held to renew plans for a National Cathedral. L’Enfant’s grand plan gave way to the Nineteenth Century growth of the city. Train tracks ran across what would become the National Mall.

At the beginning of the Twentieth Century, The United States Senate Park Commission was formed. Known as the McMillan Commission, it was named for its chairman, Senator James McMillan of Michigan. Some of the greatest American architects, landscape architects, and urban planners of the day served on the McMillan Commission, including Daniel Burnham, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., Charles F. McKim, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The Washington DC that we know today, with it’s inspiring vistas, cherry trees and reflecting pools is largely the product of this commission.

In 1902 the commission’s plan was published. Building on the work of L’Enfant, and inspired by the Cities Beautiful Movement, a grand but beautifully scaled Washington began to take shape. In her Northern reaches, plans for two beautiful houses of worship were also taking shape.

Frederick Bodley, known for his fine church designs in England, led the team designing the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul for the Episcopal Diocese of Washington. [1.] Construction began in 1907. After World War I, Philip Hubert Frohman, an American architect, took over the supervision of the work. Construction of the National Cathedral went on for most of the Twentieth Century. As good stonemasons became harder to find, work was speeded up. Then a program to train stone masons was established on the Cathedral grounds. The Gothic cathedral features beautiful bas relief sculptures of the Creation and a gargoyle that resembles French President Charles DeGaulle! A statue of Darth Vader [2.] is up there as well, sculpted by Jay Hall Carpenter and Patrick J. Plunkett. The building was completed in 1990.

Today the cathedral is a prominent feature of the Northwest Quadrant of the city.

Bishop Thomas Joseph Shahan, the fourth rector of the Catholic University of America envisioned the construction of a national shrine to commemorate the Immaculate Conception in the country's capital. [3.] He took his appeal to Pope Pius X on August 15, 1913. The Pope was excited by Shahan’s vision and Catholic University donated land on its campus in the Northeast Quadrant of the city.

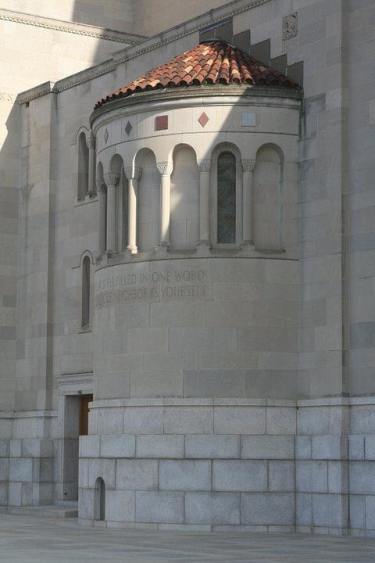

Architects Maginnis and Walsh of Boston first proposed a gothic building as well, but Bishop Shahan wanted the shrine to be bold, glorious and unique. A Byzantine-Romanesque design was chosen. The archbishop of Baltimore, Cardinal James Gibbons, blessed the foundation stone on September 23, 1920.

The Great Depression halted construction, as did the Second World War. In 1953 construction resumed and continued through the Twentieth Century. There are still mosaics remaining to be completed in the great dome, but the building is essentially complete. The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception rises above the grey buildings of Catholic University as a prominent feature of the cityscape.

Thus two great architectural testimonies of faith hold their place in the profile of our nation’s capital. Neither is supported by federal monies but the presence of both stands as a reminder that: “Behold, the nations are as a drop of a bucket, and are counted as the small dust of the balance: behold, he taketh up the isles as a very little thing.” -- Isaiah 40:15

Tower... Photo by Laney Riley.

...and tile of the National Shrine. Photo by Laney Riley.

The National Cathedral. Photo by Laney Riley.

Rose window in the cathedral. Photo by Laney Riley.

Flying butresses of the cathedral. Photo by Laney Riley.

No comments:

Post a Comment