Volume VII, Issue XI

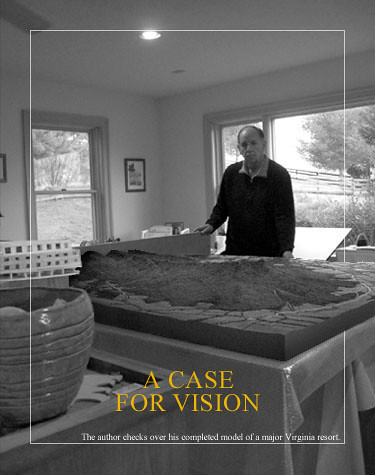

A Case for Vision VIII

© 2014 The Kirchman Studio.

What model best advances a society? What will propel us to new frontiers in creativity and to meet the needs of humankind most effectively? Again, history provides examples to learn from. We know intuitively that the American Revolution didn't happen in a vacuum. We know that John Locke's writings provided a model for Jefferson, but like any great work there is more to its creation than first meets the eye. If one takes a magnifying glass and looks closely, what might we learn? Before Bristol could revitalize itself, before the good of eliminating slavery could be accomplished that would necessitate Bristol's revitalization, there was profound societal change that would usher it in. In their book The Poverty of Nations [click to read] Wayne Grudem and Barry Asmus present the story behind the story, as it were. In 1688 England experienced its Glorious Revolution, where leaders of Parliament asked William of Orange to invade England and take the throne from James II. With an army of fifteen thousand Dutch soldiers, William overthrew James II who did not even resist his removal. The Glorious Revolution had the effect of limiting the king's power while vesting the power to govern in Parliament. Here we have a representative body assume real power and a firm check against absolute monarchy. The result was a greater pluralism in representation and what Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson hail as: "the world's first set of inclusive political institutions" in their book: Why Nations Fail. [1.]

William of Orange had been schooled in the thought of the Reformation. That Revolution, though many think of it as 'merely' spiritual, actually caused a paradigm shift in the culture as men and women were encouraged to pursue relationship with the Divine through each one's reading of the Scripture. The result was that personal literacy was encouraged, education flourished and everyone in the society was now able to work with new ideas. Jewish culture already encouraged such individual study and those cities in Europe who encouraged their Jewish communities rather than surpress them enjoyed the fruits of inventiveness and industry as well. Conversely, those who's cultures maintained the creative sector in the hands of a powerful few often surpressed this wonderful culture of creativity. The pograms of Czarist Russia and the Inquisition of Spain ultimately had the effect of squelching the healthy freedom of inquiry and exchange of ideas that propelled Post-reformation Northern Europe forward. Religious Freedom was a necessary byproduct of Reformation. It did come into being in at least limited form in some countries of Northern Europe. The desire for Religious Freedom spurred a number of diverse Faith communities to come to the new world. New England's Pilgrims and Maryland's Catholics sought it. The Anabaptists and the Presbyterians who crossed Virginia's Blue Ridge did as well. [2.]

The advancement of human freedoms seen in the Eighteenth Century might well be seen in the light of the quest for Religious Freedom. The First Amendment of our Constitution, if you read it in its entirety (not just, as some do, for the 'Establishment' clause), places Religious Freedom as a basic right and prohibits government from infringing upon it. It is a 'Negative Liberty' to be sure, but an essential one. The First Amendment also protects thought and speech from government 'oversight.' That is why the recent selective enforcement actions of the Internal Revenue Service are so unconstitutional. In surpressing Conservative and Religious speech they have become an agency of the government to trample on a hard-won expression of a basic human right! [3.]

"Let thy work appear unto thy servants, and thy glory unto their children. And let the beauty of the Lord our G-d be upon us: and establish thou the work of our hands upon us; yea, the work of our hands establish thou it." -- Psalm 94:16, 17

In 1776, more than a hundred years after the Glorious Revolution, Adam Smith wrote in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations: "That security, which the laws of Great Britian give to every man that he shall enjoy the fruits of his own labor, is alone sufficient to make any country flourish. The natural effort of every individual to better his own condition, when suffered to exert itself with freedom and security, is so powerful a principle, that it alone, and without any assistance, not only is capable of carrying on the society of wealth and prosperity but of surmounting a hundred impertinent obstructions with which the folly of human laws too often encumbers its operations; though the effect of these obstructions is always more or less either to encroach upon its freedom or to diminish its security. In Great Britain industry is perfectly secure; and though it is far from being perfectly free, it is as free or freer than in any other part of Europe." [4.] The Eighteenth Century saw the results of mankind loosed from the bonds of serfdom where he toiled under the oversight of a Lord for protection and also loosed from the constraints of the 'Divine Right of Kings,' also a supposed provider of protection. The grim reality was that such 'protection' included the obligation to fight in the king's wars, be they righteous or capricious. Meno Simonsz had resisted this policy and he and his followers endured much persecution for it. [5.]

The American Experiment owes much to the migration of persecuted Religious people to her shores. The Pilgrims landed in Massachussetts and proceeded to build their community. At first they held all things in the commons, no doubt seeing it necesary to be unified in carving out a new life in the frontier, but after a disasterous start this changed. William Bradford assigned each family their own plot of ground and since everyone 'owned' his productivity; productivity soared. The starvation and lackluster participation of some citizens in the common agriculture was changed as each man pushed his own farm to thrive. [6.] The new model, seen in the Jamestown colony as well, placed the armory in the commons but placed industry in private hands. Now a man had incentive to learn better methods, since he and his family would literally reap the benefits. This was not so much 'rugged individualism' as modern writers often surmise, but a cooperation of free individuals each pursuing their own industry, but coming together to protect themselves from common threats and coming together to bring in their bountiful harvests. Next to the armory, in the center of the commons, was the church. Faith was even more essential than dry powder for the security of the community.

When the Moravians setled in the Piedmont of North Carolina to peacefully farm, they built the town of Bethabara. At the center of Bethabara was the Gemeinhaus, where the Moravians met for worship. There was a bell that was rung several times a day to remind the faithful to pray. Bethabara was never attacked by Native Americans and in fact developed good relationships with the surrounding tribes. They later learned that hostile factions in those tribes had indeed organized a number of attacks on Bethabara in its earlier days. Sneaking up on the little community they had assumed they had been scouted out when they heard the ringing of the village bell and they rapidly reatreated! The Moravians, in fact, long enjoyed good relations with nations like the Cherokee, since single Moravians lived as a longhouse people, much as the Native Americans. There was, in fact, a large Moravian Cherokee settlement in the pre-removal era. Sadly, they were massacred in the buildup to the Cherokee Removal. The Moravians became for a time a major force in world evangelism, living the promise of the Gospel among people around the globe. [7.]

Acemoglu and Robinson note that some institutions produce great freedom and advancement while others do not. They seem to argue that institutions can be perfected but are at a loss as to how this actually happens. In the Nineteen-sixties nations around the world seemed poised to participate in the American Experiment. Colonialism was coming to an end. In African nations freed from colonialism. Beautiful African delegates in traditional robes met in gleaming new assembly halls as they proudly presided over an entire Continent emerging from Colonialism. The U. S. Constitution was frequently used as a model as these nations set a new course. National Geographic photos and articles from the period paint the picture of a bright future emerging. But as Uganda, once the 'Pearl of Africa' sank into horrible despotism; tribalism intermixed with 'anticolonial' Marxist politics resulting in the wholesale slaughter of millions; much of Africa descended into a new Post-Colonial period of darkness. Hutus and Tutsis warred in a costly conflict that destroyed their society. What happened? The models were good. But something was lacking in the foundation. Acemoglu and Robinson have no explaination as to why some institutions succeed and other, similar institutions fail. Asmus and Gruden present a compelling case that the whole model includes soundness in the culture, a soundness rooted in faith. (to be continued)

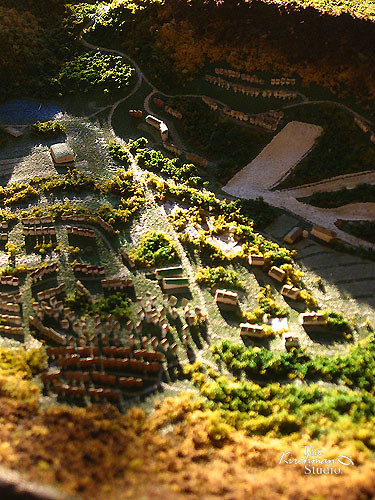

Scale model of Massanutten Resort by the Kirchman Studio.

No comments:

Post a Comment