Volume IX, Issue Va

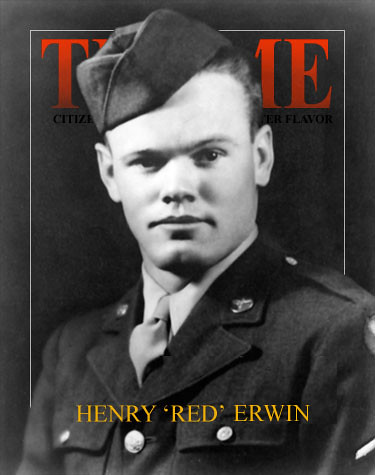

An Extraordinary Hero

Henry Eugene Erwin was born in Docena, Alabama in 1921. His coal miner father died when he was ten. Gene, as he was called then, was the oldest child and he went to work in the company store to help his struggling family. At the height of the depression, Erwin joined the Civilian Conservation Corps and later went to work in a steel mill in Birmingham. He was now his family's main breadwinner. In 1943 young Erwin joined the army. He qualified for the Air Corps and after training on the B-17 Flying Fortress he became a radio operator on the new B-29. This new Superfortress would soon strike deep into Japanese territory in the Pacific.

After getting married to his wife Betty on furlough in 1944, Erwin and his crew were assigned to Guam. Here their plane, the City of Los Angeles would make bombing runs on the main islands of Japan. On April 12, 1944, the City of Los Angeles led a formation of B-29s striking Koriyama. Part of Irwin's job was to launch phosphorous smoke bombs to lead the other planes in to their targets. As Erwin pushed the smoke bomb into the chute, something went terribly wrong. It either jammed or was blown back, exlpoding in Erwin's face. He was blinded. His flesh was burning and the plane filled with smoke. The smoke bomb, burning at 1300 degrees, had lodged itself among the bombs in the plane!

The pilots could not see. The plane began a dive. It was certain that death would come, but would it be from the certain crash or the explosion from the munitions? Then the crew saw what had to have seemed to them an apparition as Irwin, totally aflame, located the burning phosphorus bomb and grabbed it with his right hand! Holding the white-hot canister against his rib cage, he somehow made his way towards a plane window by the navigator's station. The navigator's table blocked his progress and the seconds it took to raise it must have seemed like an eternity. Fellow crewmen remember Erwin saying: "Excuse me." as he stumbled past them into the cockpit to throw the bomb out the window.

Henry 'Red' Erwin then collapsed to the floor. He was totally aflame and his distinctive red hair was burned away. The crew put out the fire and administered morphine to the man they thought to be at death's door. But Erwin never lost consciousness. In agony, he asked: "Is everybody else alright?" The plane flew to Iwo Jima where there was a hospital.

"I Don't Say I'm a Hero"

-- Henry Eugene 'Red' Erwin

'Red' Erwin talks about the events of April 12, 1944.

Now began the most difficult set of challenges for Erwin. The doctors did not expect him to live, the phosphorous in his eyes would eventually blind him if he did. He was burned over most of his body. Ironically, his Mae West (life jacket) protected his chest as he clutched the red hot bomb. He was required to wear the life jacket during missions because he couldn't swim! Doctors began removing the phosphorous from his eyes. It was a painful process as the substance had a tendency to ignite when exposed to oxygen.

Major General Curtis E. Le May rushed a recommendation for the Medal of Honor through channels, hoping to present it to Erwin while he was still alive. There was only one problem. The only Medal of Honor in the Pacific was in a locked display case in Honolulu. General Le May had been awakened at 5:00 am to sign the Medal of Honor Citation. A special plane had been dispatched to obtain the medal. Finding noone to unlock the case, the airmen assigned to the mission broke the glass, absconded with the medal, and slipped back to their waiting plane.

Erwin had been flown to the hospital on Guam, where General Le May personally pinned the medal on him, saying: "Your effort to save the lives of your fellow airmen is the most extraordinary kind of heroism I know." Through the bandages covering his wounded face, Erwin responded: "Thank you, sir."

Erwin would go on to endure 43 surgeries in the next thirty months. But what might be his greatest giving of himself was yet to come. He did survive. He and Betty raised four children and he lived to see seven grandchildren. Henry 'Red' Erwin, his right arm permanently disabled, could not go back to the steel mills. Harry Truman had issued orders that any Medal of Honor recipient, otherwise qualified, was eligible for a veterans' benefits job. Erwin went to work for the Veterans Administration as a veterans' benefits counselor. For thirty-seven years he worked with wounded veterans, especially burn victims. Though the sight and smell of burned flesh brought back memories of his own intense pain, Erwin took a special interest in encouraging these heroes.

His son, Henry E. Erwin Jr. says of him: "Dad was a man of manners; He was always polite and courteous. He rarely got angry, but when he did, he meant business. He never yelled and screamed, but he had a firmness to his voice when he was angry. ...He embodied all the ideals of the Medal of Honor. He wore them like a well pressed suit. He was honest, thrifty, and patriotic. ...He never owed a debt, never got a ticket, never was sued. He obeyed the law, attended church, and treated everyone with courtesy and respect." On January 16, 2002, Henry 'Red' Erwin died at the age of eighty.

Henry Erwin with his wife Betty and his mother.

No comments:

Post a Comment