Of all the wonderful feats I have performed, since I have been in this part of the world, I think yesterday I performed the most wonderful. I produced unaninimity among fifteen men who were all quarreling about that most ticklish subject -- Taste." -- Isambard Kingdom Brunel

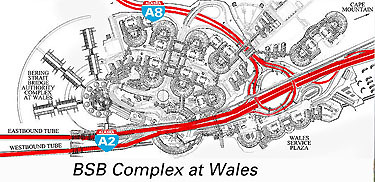

Zimmerman's complex at Wales was originally meant to be simply a construction camp and to continue as a port of entry to the Americas. It was a city in itself that seemed determined to outgrow whatever space was alloted to it. The buildings were fabricated in the same shipyards that produced the components of the great bridge. Indeed one felt like one was inside a cruise ship walking through the endless connecting corridors. Pat Zimmerman had come up with her husband in the early days but hated the hallways. Her poor circulation made the cold outside unbearable, but the "Labyrinth of Exile," as her husband called the sprawling complex, simply depressed her.

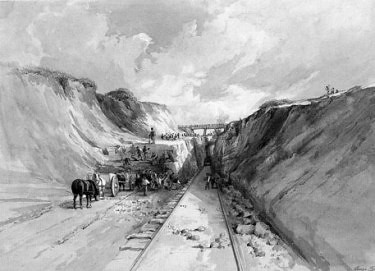

The "Labyrinth of Exile."

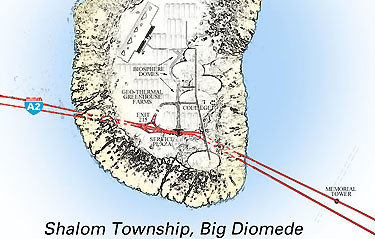

He'd taken the name from a biography of Theodor Herzl by that title and it stuck. It was a machine produced environment created of necessity. In great design rooms people like Pat's granddaughter were creating wonders like the Big Diomede Biospohere and the tundra farms. Still, if the design studios were a rich world, the connective tissue of the hallways and public spaces was an impoverished one. The small band of overachievers engaged in this great work required little in the way of diversions. Pat could not survive in such a sterile world. With great sorrow, Rupert resigned himself to the life devoid of family that so many of the world's great innovators seemed to be sentenced to.

The Biosphere and the calling of the Greenes was born largely out of a desire to correct this. Pat had been initially impressed when she visited and saw the richness of Kris' little house in contrast to Rupert's sterile hallways. She thought it an anomality though and didn't want to lose the circle of supportive friends she had in Virginia. The Biosphere was nice, but it was a small circle of light in a very large entity that seemed to Pat more like an oil camp on steroids. If she took notice of how Rupert seemed drawn to the Biosphere and its gardens, she must have been skeptical of it. Rupert had always befuddled his wife. He loved to photograph the flowers in their Virginia garden but often forgot to water them. He was her own real-life version of James Thurber's fictional "Walter Mitty," often seeming to inhabit another world. Unlike the fictional Mitty, Zimmerman was building his 'other world' and a world starved for such endeavors embraced him for it.

Zimmerman wondered at how such basic needs as breathing and the need to walk required no motivation, yet standing in a man's full potential eluded the ability to teach. He devoted himself to studying how men might develop the hunger to rise to the height of their potential and walk in it. He sparred often with Greene over how to inspire men. Marx had called religion the "Opiate of the Masses," yet Rupert thought it was more like the pills drivers took to keep them awake on the long road to Yakutsk. It was, to Zimmerman, a necessary boost in the driver's inate alertness. "Truck Wrecks on the Siberia Highway" were a macabre subject of continual fascination on the internet. The fact that these incidents were few and often photoshopped did nothing to shatter the myth. The road was truly dangerous.

Rupert pondered great moments in history. There was the Battle of Trenton where a band of weary patriots turned the tide of America's Revolution. The American response to the attack on Pearl Harbor and the resolve to win the world's most horrific war on multiple fronts preceeded the establishment of Herzl's vision. Yet in his own lifetime, Zimmerman had seen the 2001 attacks on New York and Washington met with an initial resolve that soon withered. America resigned herself to whatever forces the world would throw it. Such Fatalism went against Zimmerman's constitution. As students of engineering found their way to his studios, Zimmerman rounded out their education with a healthy dose of history... and that history full of the stories of overcomers!

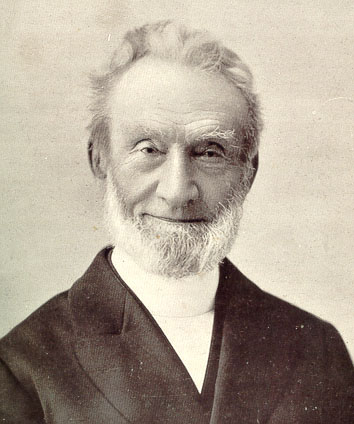

Rupert's school also looked at life through the Macro-lens as well. He learned that infants, no different from his granddaughter he surmised, had been placed in an orphanage in Tehran, Iran. The attendants of this place merely fed and changed the infants. There was no cuddling, no interaction, there simply wasn't time for that. An appalling percentage of these precious souls never sat up, never walked... they simply died. He studied long and hard the transformation in society's view of orphans in the Victorian Era. Men like Charles Dickens and George Müller had seen the wretched street urchins most people despised as jewels to be polished. Müller, relying solely on Divine provision, built five large houses for Orphans at Ashley Downs in Bristol, England. He trained the girls to be nurses, teachers, clerical workers and domestics. He apprenticed all the boys in various trades. He was excoriated for training these unwanted children "above their station." He ignored the critics.

George Müller.

When William Wilberforce had ended the slave trade in the British Empire, he had thrown the city of Bristol into economic depression. The port there was heavily devoted to that wretched business and suffered heavily when it was brought to a sudden halt. The unintended consequence had been a rise in children condemned to a life of poverty. Ending the vile business of enslaving Africa's children had resulting in England's society spurning the needs of her own.

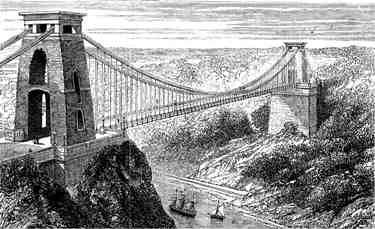

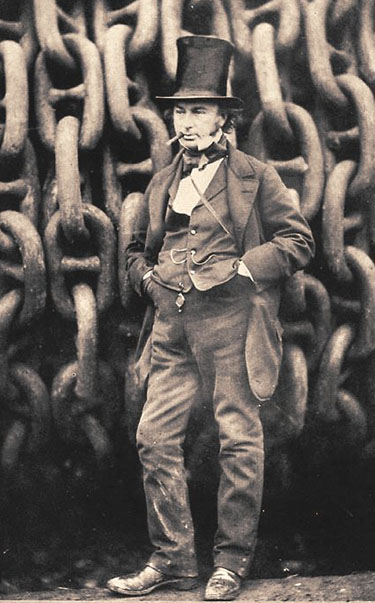

In 1831, 24 year old Isambard Kingdom Brunel was awarded a contract to bridge the Avon Gorge. It was the dream of a prosperous wine merchant who provided the initial funding. The completed bridge would become the symbol of the city, but lack of funding dogged the project. It took thirty years to complete it. For years only the towers stood completed. In 1833 Brunel began work on the Great Western Railway, which would become the instrument of Bristol's economic revitalization. The nicknames: "Great Way Round" and "God's Wonderful Railway" seem to describe well Brunel's great work.

Brunel's Clifton Suspension Bridge became the symbol of the City of Bristol.

Building the Great Western Railway.

Zimmerman and his apprentices studied the work of men like Brunel, who in the Nineteenth Century had built shipyards and had designed the first propeller driven transatlantic steamship. Like the steelworkers in Bodine's photographs, they seemed involved in the pouring of some fiery inventiveness beyond their ability to create on their own. In fact, the stuff of creativity seemed dangerous, its mishandling capable of reducing its handler to ash. The more Zimmerman accomplished, it is safe to say, the less ownership he felt of the work he'd seen accomplished.

Children at Ashly Down.

Children at Ashly Down received education and training for future employment. the day started at 6am for the orphans, normal for working-class children of Victorian times.

While boys would be placed in apprenticeships at age 14, the young ladies would remain until 17. They received training to be Nurses, Teachers and Domestic Servants [as the group in maids' uniforms above].

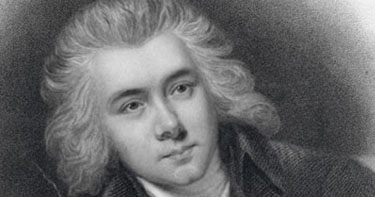

William Wilberforce.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

(to be continued) [click to read]

[click to read ]

Copyright © 2015, The Kirchman Studio, all rights reserved

No comments:

Post a Comment